En route to his recent ATP Masters 1000 title in Madrid, Alexander Zverev notched his first clay court victory over Rafael Nadal. Zverev beat Nadal twice before their Madrid encounter, but both victories came on indoor hard courts. Playing Nadal on clay is a different animal though. His confidence on clay is sky high, the higher bounces magnify Nadal’s ability to hit the ball with heavy topspin, and the slower conditions tend to make matches more physical, which Nadal relishes.

After Zverev took the match 6-4 6-4 in the quarter finals in Madrid, the two were set for a rematch a week later in the quarter finals of the ATP Masters 1000 in Rome. This time it was Nadal, who came away with the 6-3 6-4 victory. Looking at the statistics from both matches, we can catch a glimpse of the adjustments that Nadal made, and how he was able to tilt the way the match was played in his favor in Rome more so than in Madrid.

Extending the Points

Let’s first take a look at the distribution of the different rally lengths from the Madrid match, which Zverev won.

| Total Points | Percent of Total | Zverev | Nadal | Advantage | |

| 0-4 shots | 65 | 59.63% | 36 | 29 | Zverev +7 |

| 5-8 shots | 29 | 26.61% | 18 | 11 | Zverev +7 |

| 9+ shots | 15 | 13.76% | 6 | 9 | Nadal +3 |

Almost 60% of the points in Madrid were shorter than 4 shots, and over 85% were shorter than 8 shots. The average rally length for the match was 5.9 shots. It was in these shorter rallies where Zverev won the match. Once the rally extended past 9 shots, it was advantage Nadal; but since those rallies counted for less than 15% of all points, it was not enough to swing the match in Nadal’s favor.

Going into the match in Rome, I would assume that one of Nadal’s goals was to work his way into the point, extend the rallies, and make the match more physical than was the case in Madrid. Let’s examine the same statistics from Rome.

| Total Points | Percent of Total | Zverev | Nadal | Advantage | |

| 0-4 shots | 44 | 34.92% | 25 | 19 | Zverev +6 |

| 5-8 shots | 50 | 39.68% | 22 | 28 | Nadal +6 |

| 9+ shots | 32 | 25.40% | 12 | 20 | Nadal +8 |

Mission accomplished for Nadal. Zverev still won the 0-4 shot rally length, but the percentage of total points in that particular bucket dropped from about 60% in Madrid to only about 35% in Rome. Conversely, the contribution of the 9+ rally length increased from about 14% in Madrid to over 25% in Rome. Combine those two, and the average rally length in Rome jumped to 7.5 shots compared to the 5.9 average in Madrid. Furthermore, Nadal was able to reverse the 5-8 shot rally length to his advantage, and maintain his dominance in the extended 9+ shot rallies.

How exactly was Nadal able to extend the rallies in Rome compared to Madrid? By going into Zverev’s backhand more, and by hitting spinnier, heavier groundstrokes.

Targeting the Zverev Backhand

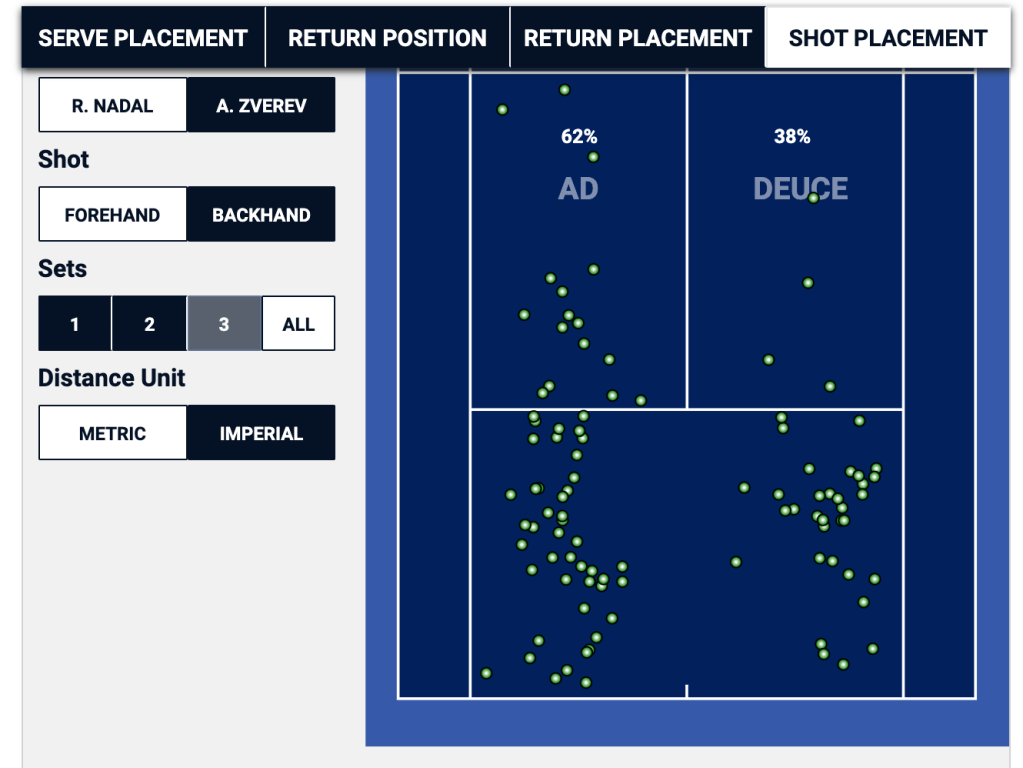

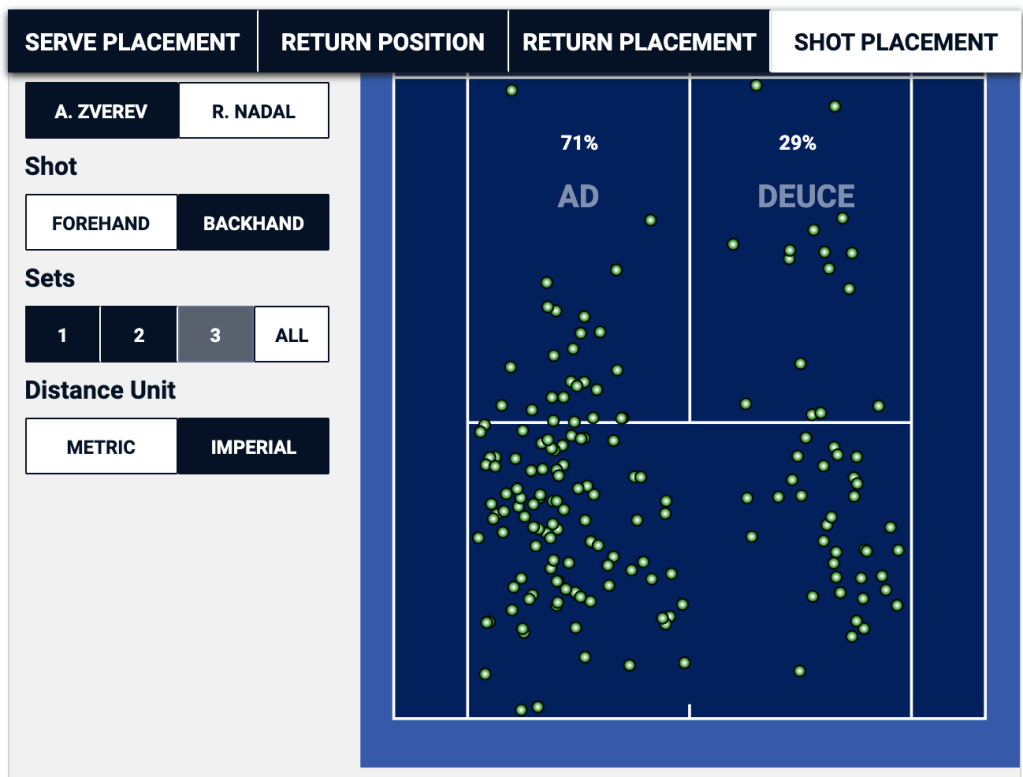

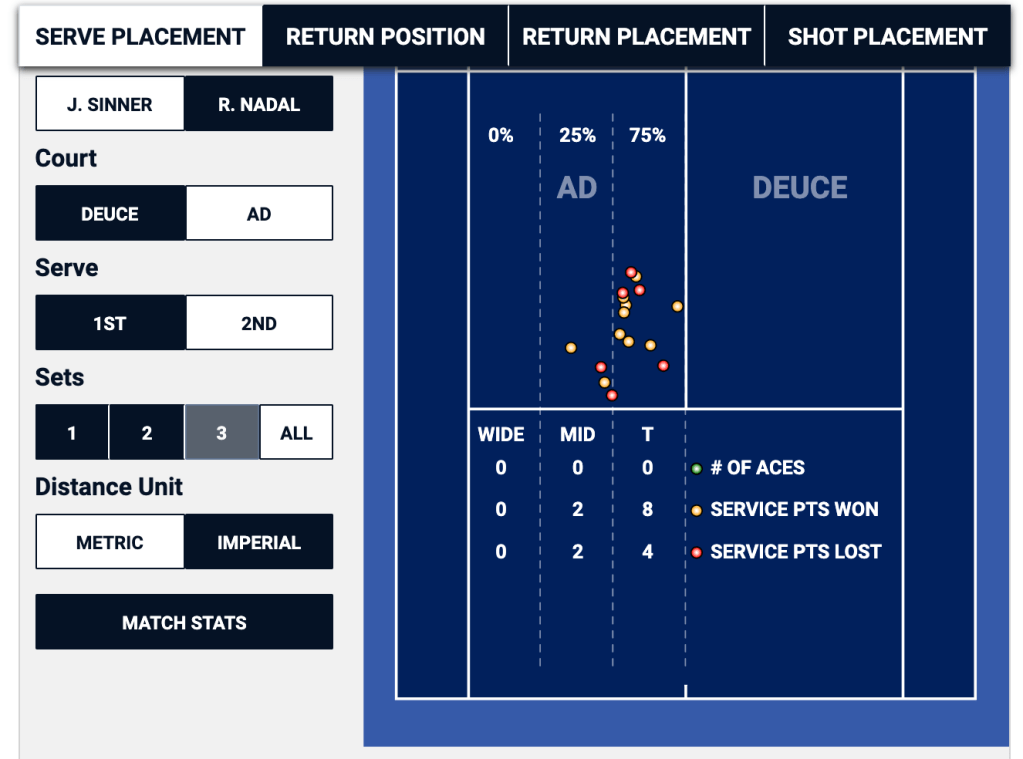

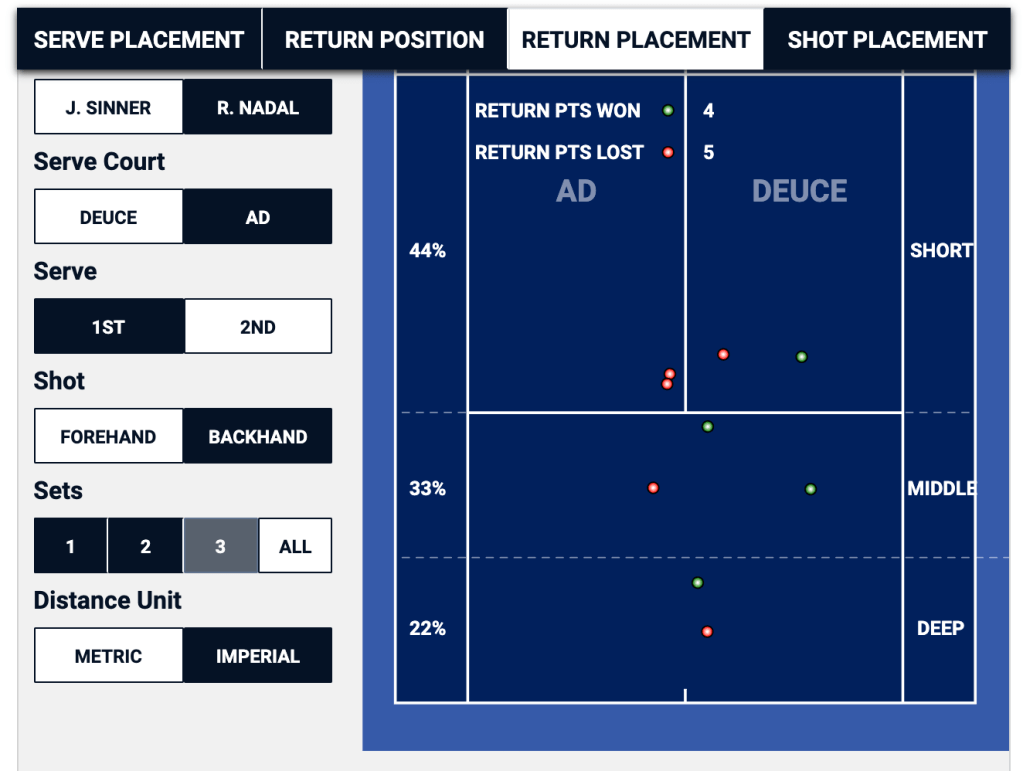

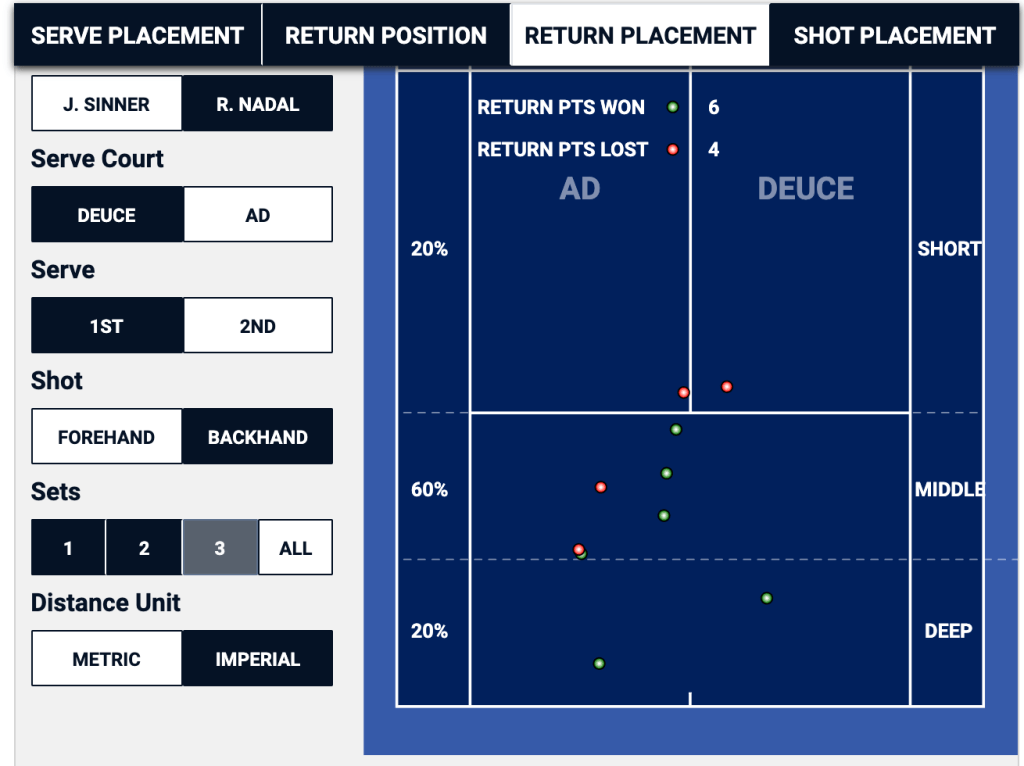

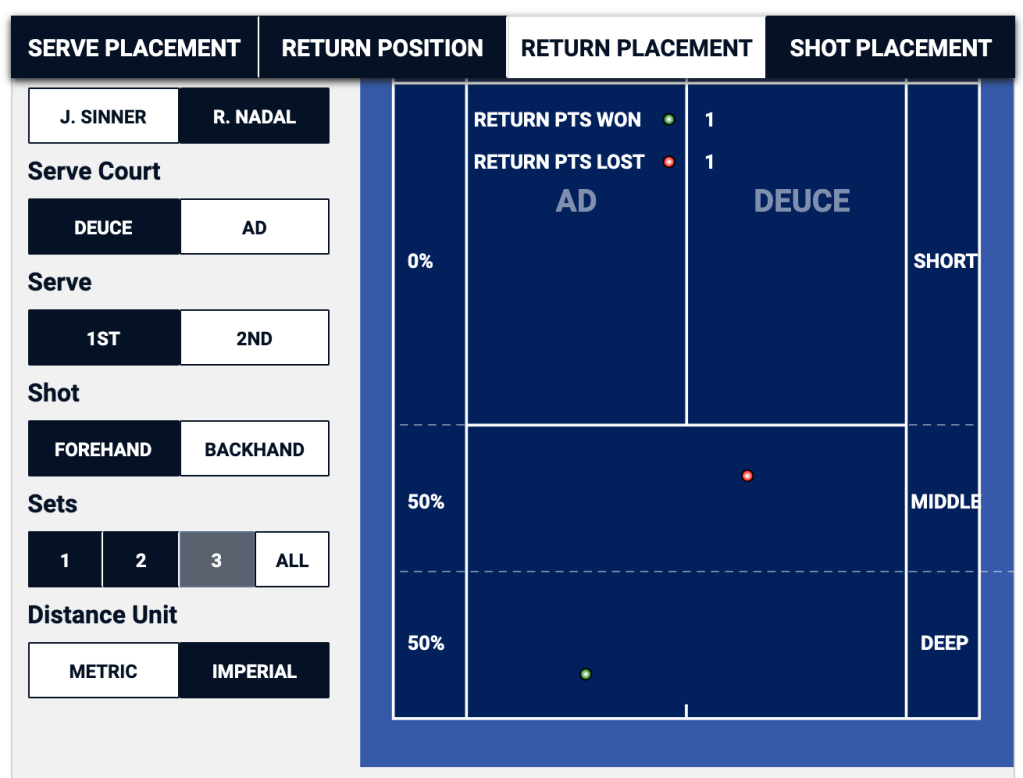

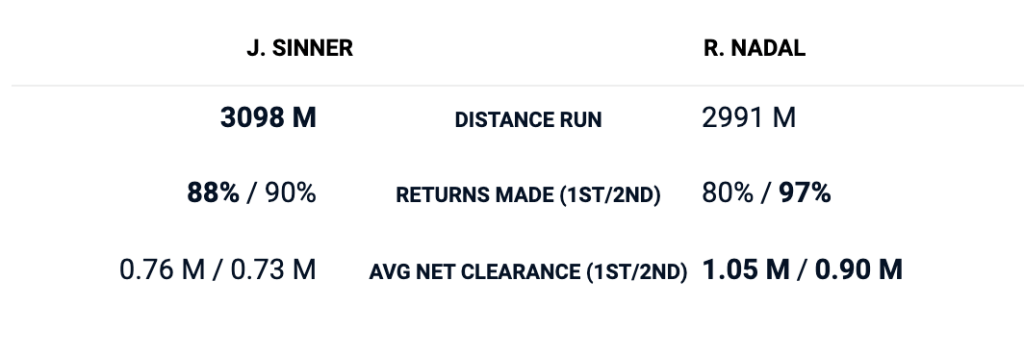

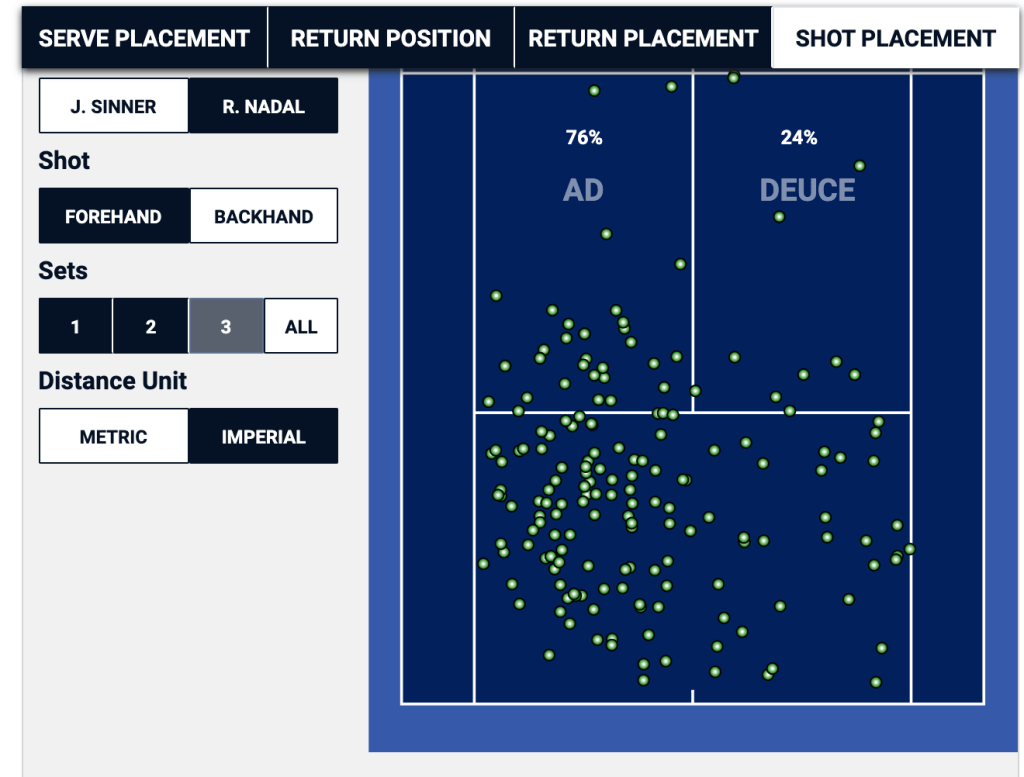

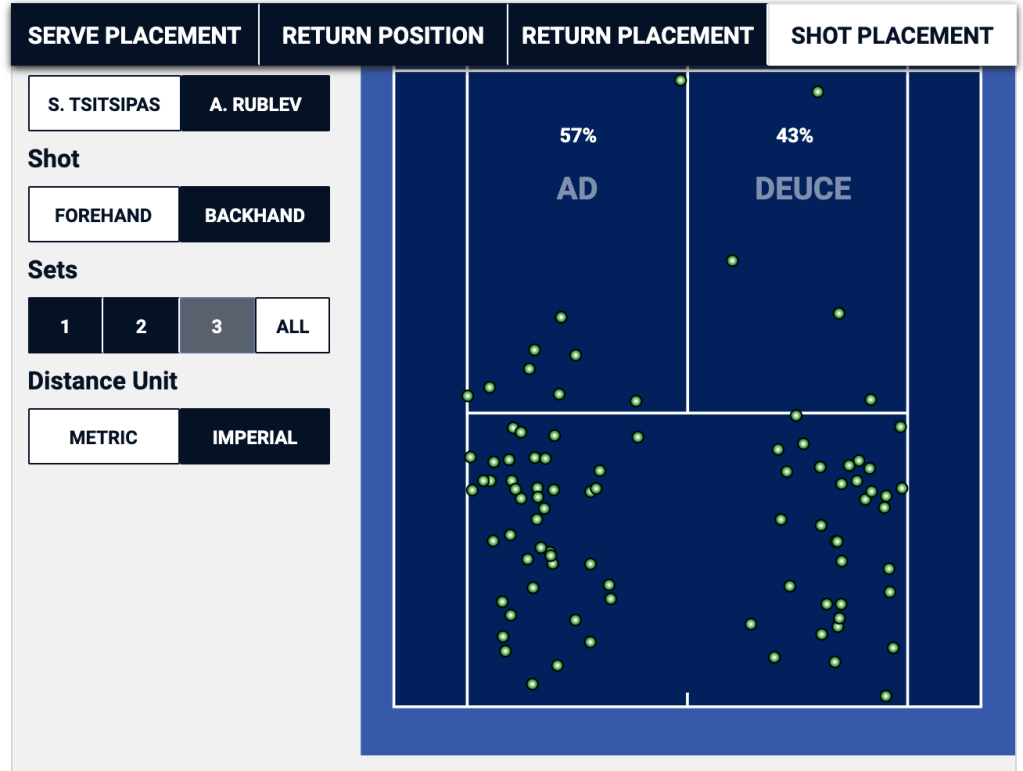

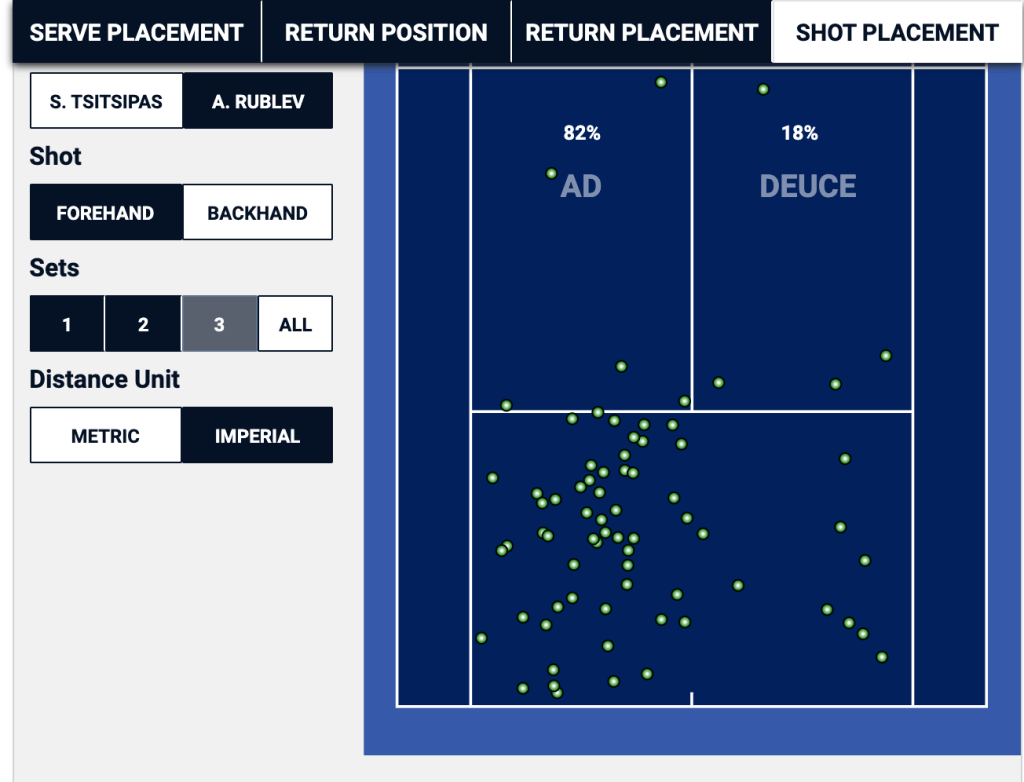

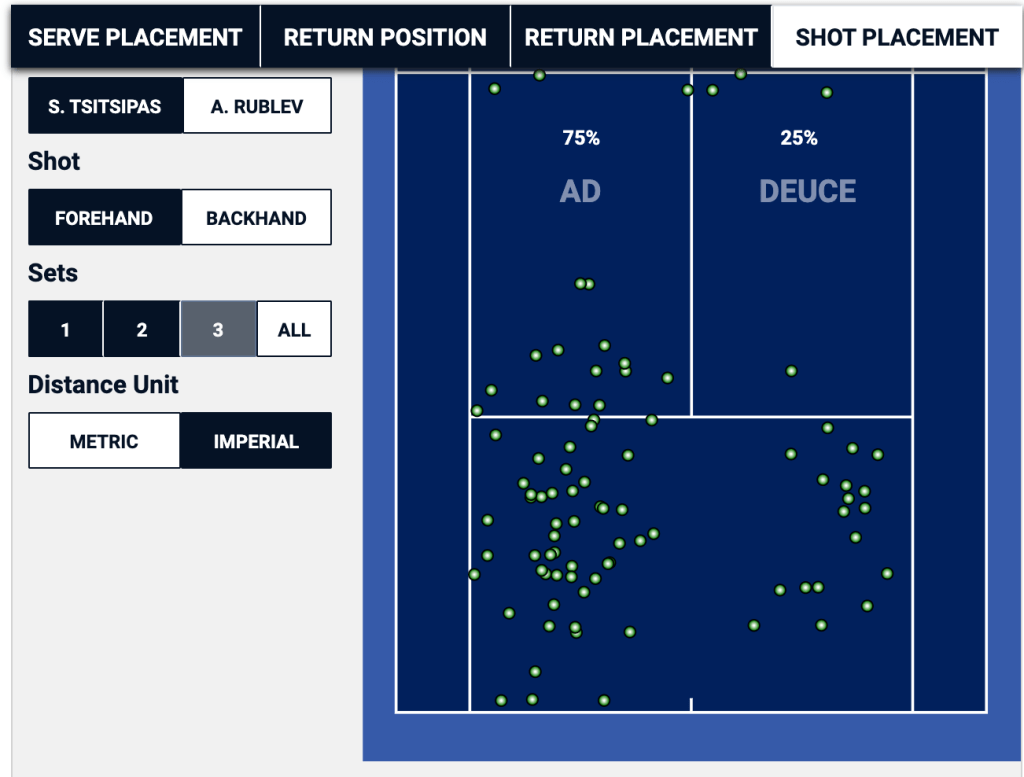

Once the point got started, Nadal’s strategy in Rome was much more focused on hitting through the Zverev backhand than was the case in Madrid. Let’s look first at the comparison of Nadal’s forehand targets from both matches:

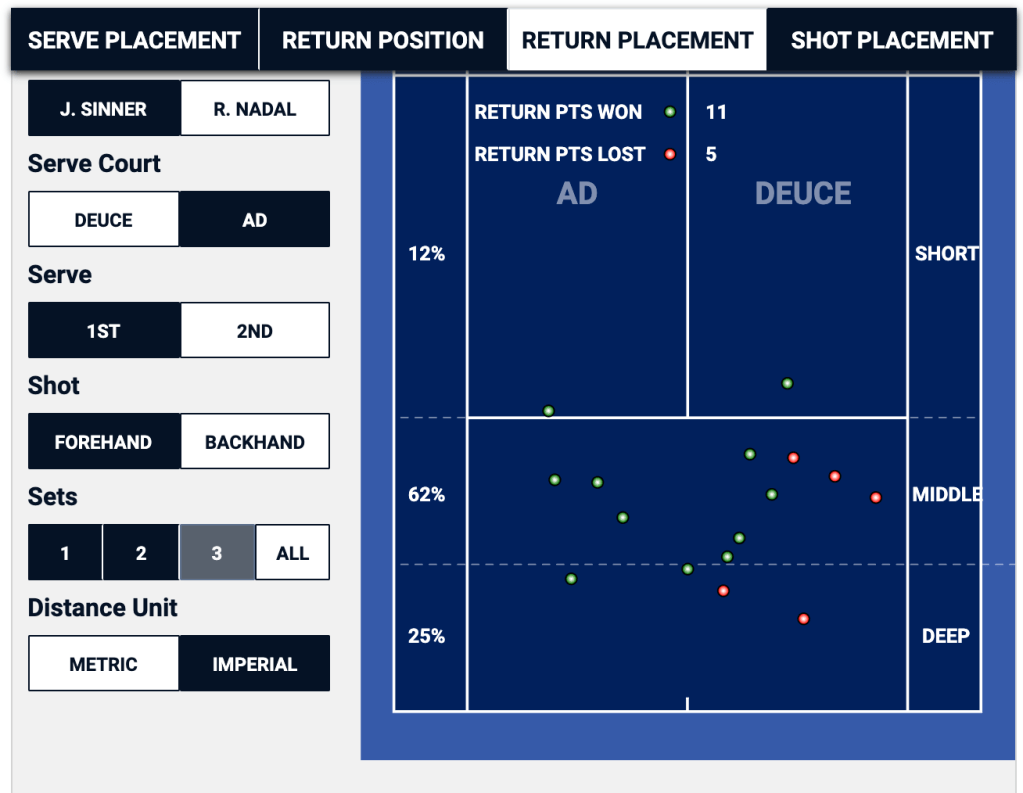

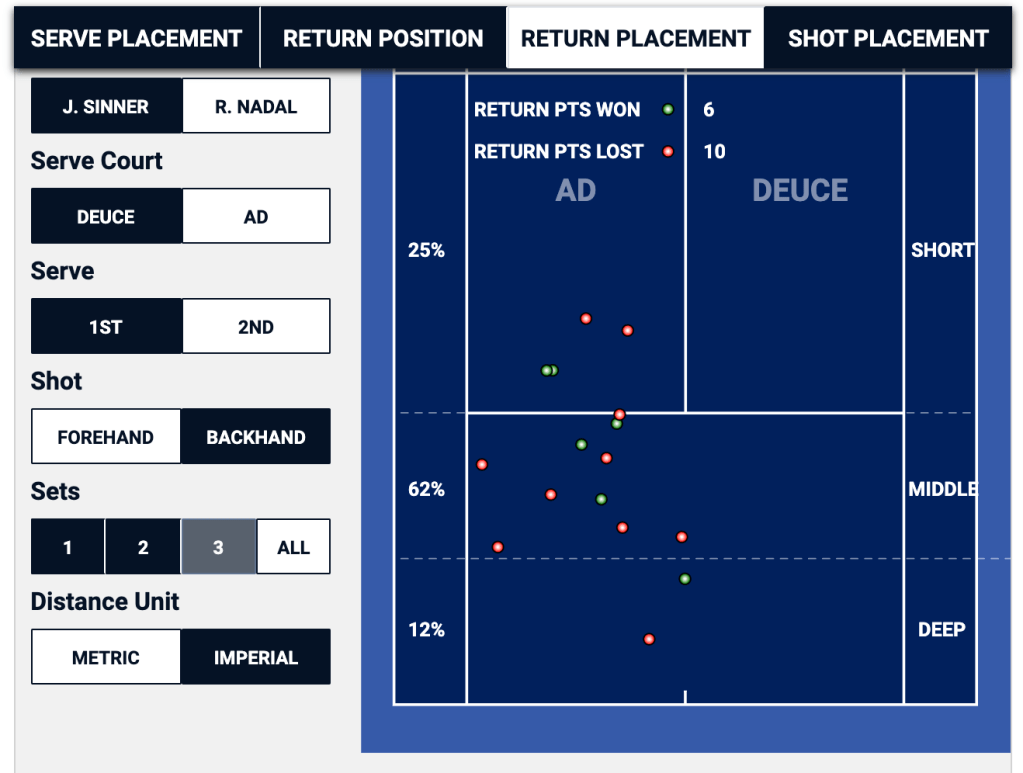

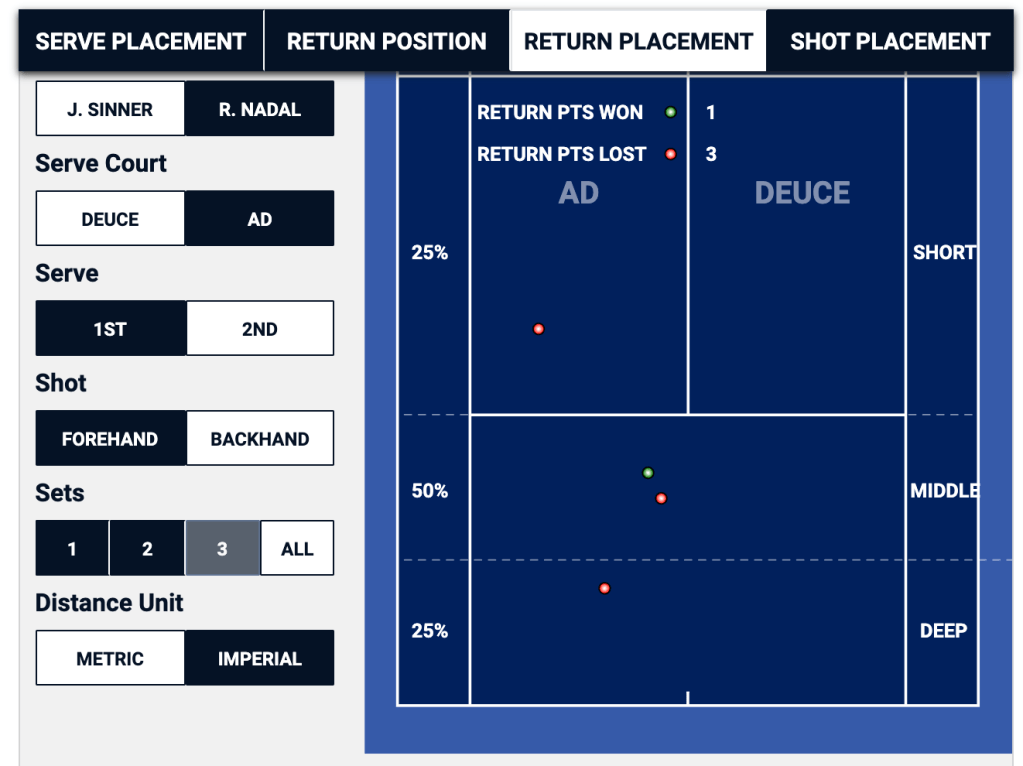

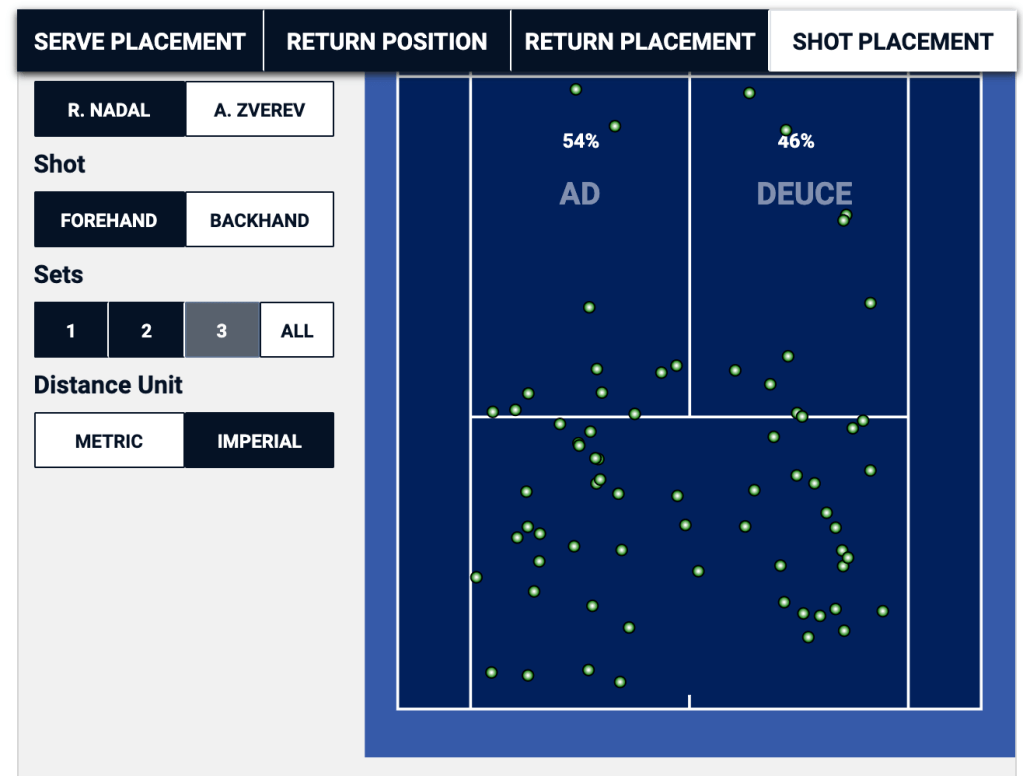

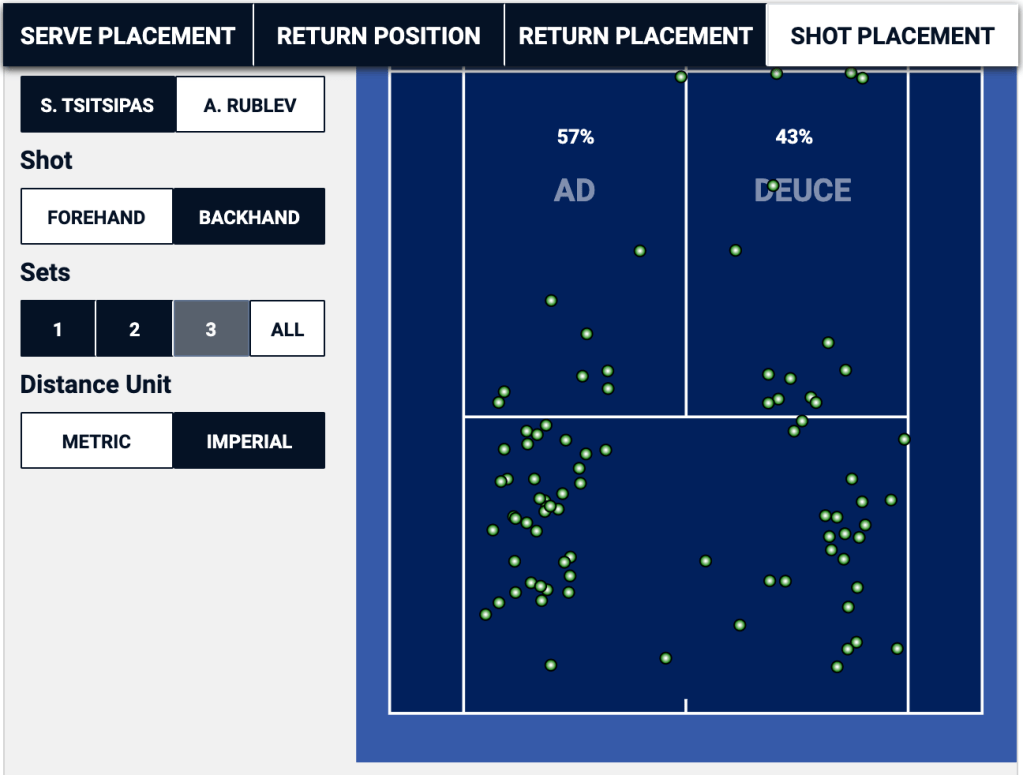

The left image are Nadal’s forehands in Madrid, where he lost, and the image on the right is Nadal’s forehands in Rome, where he won. There is about a 10% increase in Nadal’s forehands being aimed cross-court into Zverev’s backhand. The difference is yet more pronounced on Nadal’s backhands:

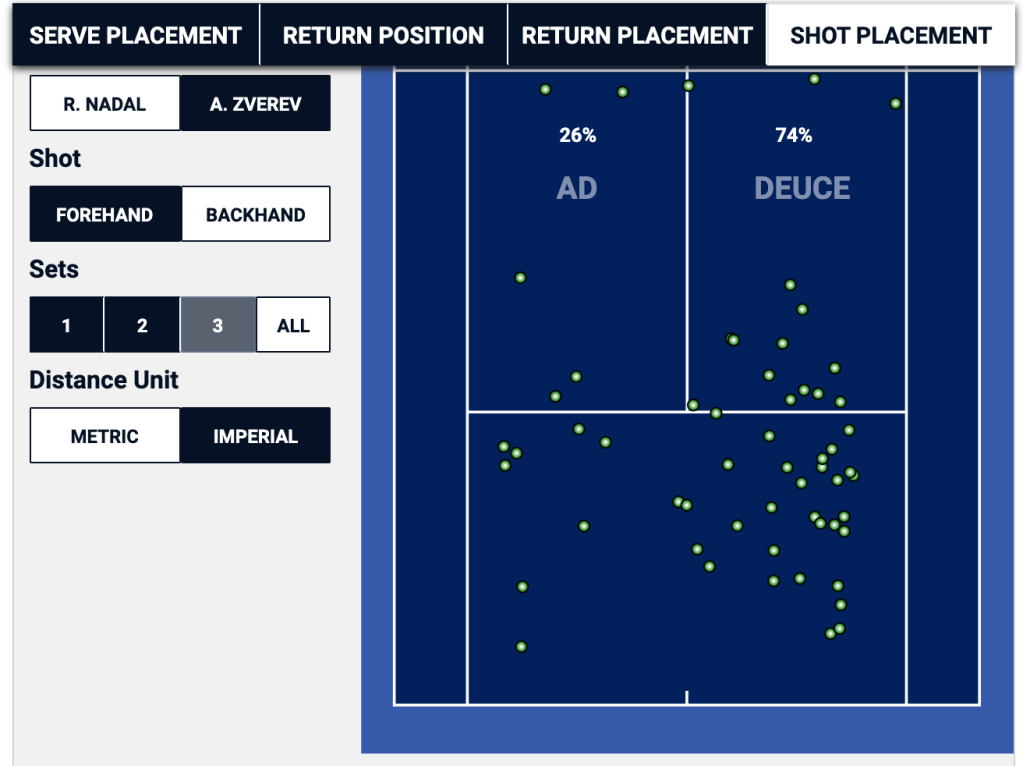

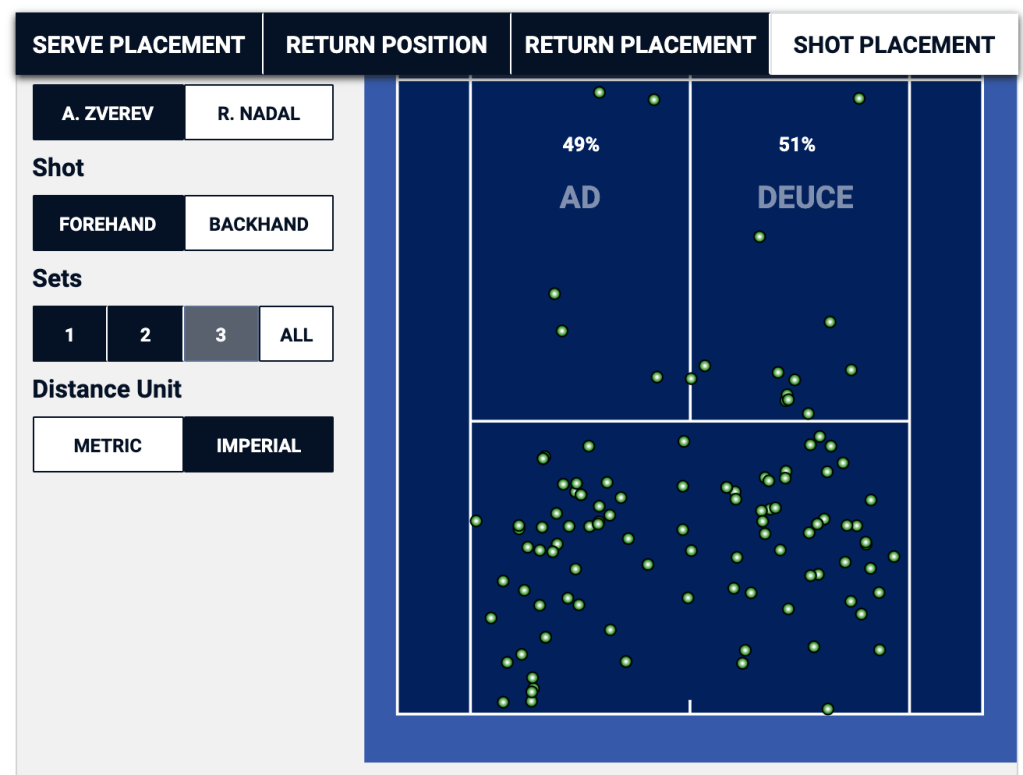

The left image is once again Nadal’s backhands from Madrid. In that match, Nadal hit 3 out of every 4 backhand cross-court into Zverev’s forehand. In Rome, Nadal made sure to stay away from that particular pattern more often, and his backhands were split about evenly between cross-court and down the line. Also, notice the higher frequency with which Nadal’s backhands were landing deeper in the court in Rome than was the case in Madrid. Depth is one of the best ways to gain control of the point in a rally, and it was surely a contributing factor in Zverev committing 31 rally unforced errors in Rome as compared to just 10 in Madrid.

Heavier Spin on Groundstrokes

Not only did Nadal get his groundstrokes – especially backhands – deeper into the court in Rome, his strokes were also “heavier,” hit with more topspin. Below is a table comparing the average RPMs on groundstrokes from both the Madrid and the Rome matches.

| Nadal FH | Nadal BH | Zverev FH | Zverev BH | |

| Madrid | 3,069 rpm | 2,378 rpm | 2,893 rpm | 1,529 rpm |

| Rome | 3,183 rpm | 2,578 rpm | 2,830 rpm | 1,500 rpm |

| Difference | +114 rpm | +200 rpm | -63 rpm | -29 rpm |

While Zverev was hitting his groundstrokes flatter in Rome than he did in Madrid, Nadal really cranked up the topspin, especially on his backhand wing. Knowing that balls with more topspin tend to bounce higher than flatter strokes, and combining that with the groundstroke distribution patterns, we can try to guess Nadal’s baseline strategy in Rome: try to get the ball up high on Zverev’s backhand, making it harder for him to attack from that part of the court. Now, Alexander Zverev is listed at 6’6″, so this is no easy feat.

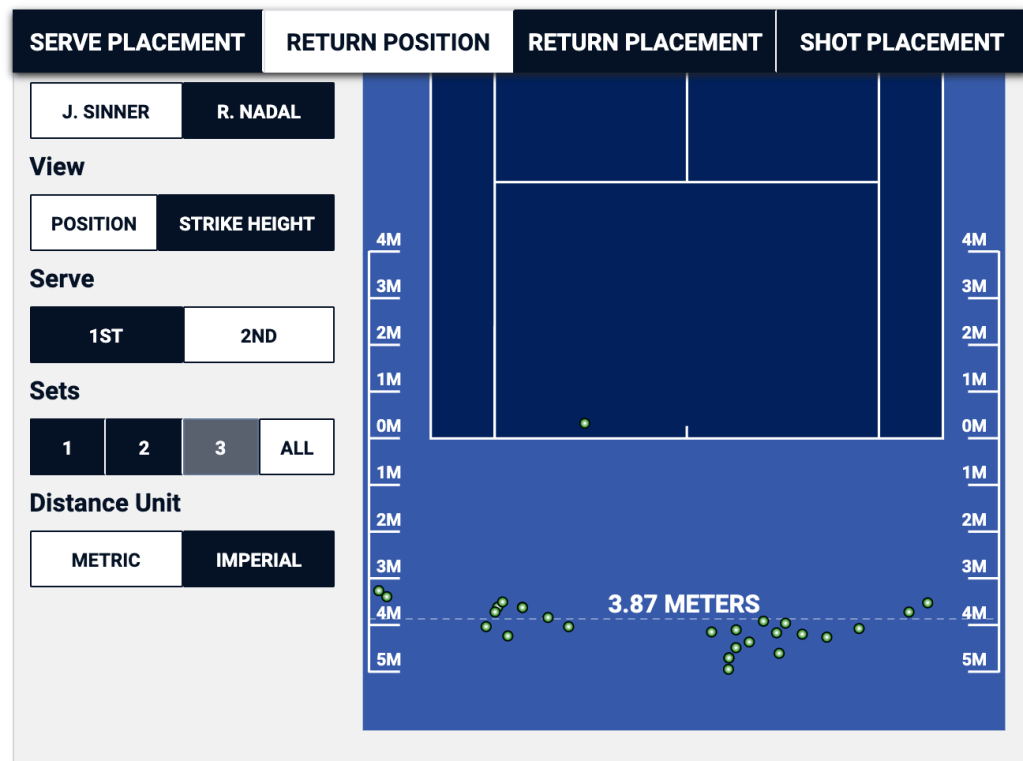

It would be great to see the average net clearance of Nadal’s groundstrokes in the match, but I can’t seem to find that statistic on the ATP website. The best I can do is compare the average net clearance on Nadal’s second serve returns, which were hit about 0.81m above the net in Madrid, and about 20cm higher – 1.03m above the net – in Rome. It is certainly not hard evidence, but it points in the same general direction as the higher rpms on the groundstrokes: get the ball higher on Zverev.

Getting the ball deep and under heavy spin into Zverev’s backhand forces Zverev into a decision. Option one is to try to take the ball on the rise, before it gets up above his shoulders. The timing of that shot is tricky even for the best players in our sport, and given how flat Zverev’s backhand is, the margin for error is slim. Alternatively, Zverev can back up and wait until the ball drops back down into his strike zone. That, however, puts him in a defensive position way behind the baseline – minimizing his chance to attack – most likely extending the rally – and playing right into Nadal’s hands. Pick your poison time for Zverev.

Alexander Zverev was able to get the best out of Rafael Nadal in Madrid by keeping the majority of the rallies short. Nadal countered in Rome with a strategy designed to extend the rallies, and trying to get Zverev uncomfortable in the ad side of the court. Should these two face-off at the French Open, one of the factors deciding the outcome of the match will be the length of the rallies. If Zverev can keep the match a first-strike battle, he has a chance. Otherwise, with every extra groundstroke hit, Nadal’s advantage will keep mounting.